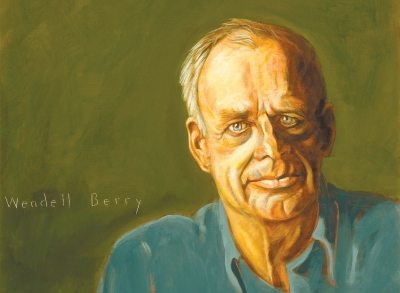

Wendell Berry and prepare students for “good jobs”

go through Terry Heick

The impact of berries on my life is therefore immeasurable with my teaching and learning. He has a place in larger conversations about economy, culture, and profession in the notions of scale, limitation, accountability, community and thoughtful thinking, if not politics, religion, and elsewhere where common sense is insufficient.

But what about education?

Here is a letter written by Berry in response to the call for “shorter work week.” I left the argument to him, but it made me wonder if this idea has a place in the new form of learning.

What do we miss when we stick to education and do things that are “obviously”?

That is, as a close alignment between compliance with results-based learning practices, standards, learning objectives and assessments, and careful scripting on both horizontal and vertical levels, there is no “gap” – what assumptions are embedded in this persistence? Because in the high-risk game of public education, each of us collectively “all”.

More directly, are we doing “good jobs” for learners or just preparing for academic fluency? What is the role of public education?

If we tend toward the former, what evidence would we see in the classroom and in college?

Perhaps most importantly, are they mutually exclusive?

Wendell Berry

progressin the September “Editor’s Note” by Matthew Rothschild and John de Graaf’s article (“Reduce work, more life span”), both offer “less work” and 30-hour work weeks, which are essential, and it’s essential.

Although in some cases I would support the idea of a 30-hour work week, I don’t have any absolute or undisputed ideas about it. Only when respect for careers and slogan substitute discourses can one raise a general need.

Indeed, the industrialization of almost all forms of production and service is full of meaningless, derogatory and boring “work” and is essentially destructive. I don’t think there is a good argument for the existence of this kind of work, and I hope it eliminates it, but even its reduced economic changes are not yet defined, let alone the “left” or “right” advocated. As far as I know, neither of these aspects makes a reliable difference between good and bad jobs. Shortening the “formal work week” while agreeing to continue bad work is not a solution.

The ancient and glorious idea of “profession” is simply that each of us is God, our gifts, or our preference for good jobs that we are particularly suited to. What is implicit in this idea is the possibility that we may be willing to work, and there is no necessary contradiction between work and happiness or satisfaction.

Only when there is no idea of any viable career or good job, can the difference implied in phrases such as “feed less, more life” or “work-life balance” is like commuting here every day.

But, even when we are most painful and harmful at work, won’t we live?

Isn’t this the reason why we object (when we object) to bad work?

And, if you are called music, agriculture, carpentry or rehabilitation, if you make a living by calling, if you use your skills well and can use your job well, so be happy or satisfied at work, why do you have to do less?

More importantly, why do you think your life is different from it?

Why shouldn’t you be bothered by some official methods and do less?

A useful discussion on the subject of work will raise many questions that Mr. Degraf overlooked:

What job are we talking about?

Have you chosen your own job or did you do the way to make money under forced circumstances?

How much wisdom, feelings, skills and pride are used in your work?

Do you respect products or services that result your work?

Who do you work for: manager, boss or yourself?

What are the ecological and social costs of your work?

Without such a question, we will not see reasons beyond the assumptions of Mr. De Graaf and his work and life experts: all work is bad work; all workers are unfortunate and even helpless in relying on their employers; this work and life are irreconcilable; and the only way to solve the problem is to shorten the work week, thereby distributing bad things among more people.

In theory, I don’t think anyone can respectfully oppose the claim that “reducing the hours rather than laying off employees” is better. “But this increases the likelihood of a decrease in income, and therefore the “lifetime” is reduced. To this end, Mr. Degraf can only provide “unemployment benefits”, one of the more fragile “safety nets” of the industrial economy.

How will people have something to do with “more life” and “more life” is the result of “fewer work”? Mr. De Graaf said they “will exercise more, sleep more, garden more, spend more time with friends and family, and drive less.” This happy vision comes from a not long time claiming that in the spare time of buying “labor-saving equipment” people would visit libraries, museums and symphony orchestras.

But if the liberated workers drive More?

What if they recreate themselves using off-road vehicles, fast food, fast food, computer games, TV, electronic “communications” and various porn genres?

Well, that would be “life”, said to be “life”, anything can work.

Mr. De Graaf proposed another questionable assumption that the work is static quantity, reliably available, and can be divided into quite sufficient sections. This believes that one of the purposes of the industrial economy is to provide employment to workers. Instead, one of the purposes of this economy has always been to transform independent farmers, shop owners, and businessmen into employees, then use employees as cheaply as possible, and then replace them with technical alternatives as soon as possible.

Therefore, there may be less working hours for splits, where more workers separate them and less unemployment benefits.

On the other hand, a lot of work needs to be done – ecosystem and watershed restoration, improved transport networks, healthier, safer food production, soil protection, etc. – and no one is willing to pay for it yet. Sooner or later, such work must be done.

We may end up working longer working days to avoid “live” but to survive.

Wendell Berry

Port Royal, Kentucky

Mr. Berry‘s initially appeared in progress (November 2010) Response to the article “Less work, more life.” This article originally appeared in utne.