How to create a story walk

I took my dog for a Saturday afternoon walk in the park next to my house, which has a story walk. If you’ve never had the pleasure of visiting, the Story Walk is a fun, interactive way to enjoy reading while spending time outdoors.

In Story Walks, pages from picture books are unpacked, laminated, and displayed along a walk or garden. Luckily for me, the library near the park where I walked religiously maintains “story walks” that change out the storybooks according to the seasons. I read while my dog goes for a walk.

In the spring, I look at Eric Carle’s work next to the daffodils Very hungry caterpillar Gain weight.

In the summer, I wear flip-flops and sympathize with Jabari Jabari jumpas he debated whether he should physically jump from a height into a pool.

Autumn, inspired by Lois Ehlert Ye RenI collect dark red maple leaves and yellow birch leaves.

In the winter, as I trudged through the snow, I listened carefully for the calls of the great horned owls, just like the girl and her father in the show. owl moon.

In this special park, story walks always consist of picture book pages. Familiar picture books. The kind you hear in the arms of your parents and grandparents. The kind of picture book that has a feeling of love.

Over the course of the season, I started to notice something about this story walk: People of all ages enjoy these stories. I started wondering if my middle school students would enjoy story walks.

I thought they would, so I set out to make one.

How to create a story walk

1. First, choose a book, short story, or poetry collection.

Make sure your selections work well across sections. For stories, choose books with less than 20 pages/section. For poetry, choose three to six poems that fit the theme. Plan for outdoor activities to match or complement (or at least not conflict with) the works in the Story Walk.

2. Divide the piece into pauses.

Break the story or poem into several stations (one page or poem per station). Each site will be displayed on a sign or poster so students understand the sequence.

3. Prepare book pages or poems.

Print large, easy-to-read copies of each page or poem. Laminate them to protect them from the weather.

4. Create a road map.

Choose a safe, accessible path around school. It can be along fences, around playgrounds, school walls, or maybe even along nature trails. (If it’s too cold, too hot, or rainy outside, story walks can be moved indoors, in the hallway or library.)

5. Publish your page.

Use string, zip ties, or tape to secure each laminated sheet to a tree branch, fence post, or wall. Check visibility and distance. Keep them at eye level with students. There is enough distance between each stop to allow for activity and even some chatting. In fact, you could even include discussion questions about the poem or how students responded through activities.

6. Share, celebrate and reflect.

Come together at the end and ask students to share what they loved most about the story walk. Families of students are invited to enjoy the walk as well. It can even become interactive. For example, ask students to describe their favorite sites (and then hang some of the best illustrations).

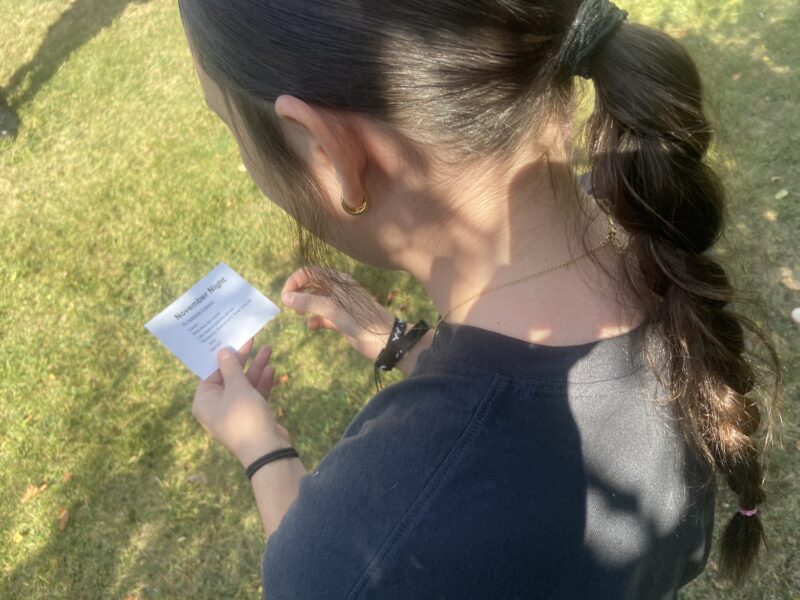

In our classroom we have been reading poetry so I decided to do a poetry story walk. I found and made miniature copies of fall themed poems. Instead of laminating them, I took out reusable dry erase pocket folders (the kind that already have reinforced holes in the top). In each folder, I packed enough poems so that all 130+ students could have a copy of each poem.

In preparation for the morning, I set out to find three sites. I found three worthy branches to hang poems on, and I made sure to give them enough distance to make this story walk-turned-poetry ramble feel like we were getting some exercise.

Expectations for story walks

Taking more than 30 teenagers outdoors on a story walk was a very brave task. It’s good to keep your expectations in check. Here are some useful expectations to discuss with students before departure.

1. The sound should match the settings.

For this activity, explain that the indoor sounds will be used outdoors. Students should be able to hear the reader’s voice. It is forbidden to yell at your friends across from you.

2. Movement is part of the process.

A calm approach to each poem is expected. It’s lovely to lean against a tree and listen or read. It’s okay to stretch out on the grass. Picking up an acorn and throwing it at a friend’s head? no OK

3. Respect space.

Talk about what it means to be a steward of the land. Do not trample plants. Don’t litter (in fact, pick up trash – your own and those left by others). Don’t climb where you shouldn’t.

4. Pay attention to your senses.

How does being outdoors affect people’s understanding of reading? What do students hear, see, and feel? For older students, it may be prudent to bring a small notepad or clipboard to take notes.

Why story walking is a good idea

It is truly extraordinary to watch students walk out of the classroom and into the story. The weather was very nice when we went out for a walk. The sun was shining brightly and a gentle breeze rustled the leaves above our heads. As we read Gary Soto’s “October,” the words seemed to come alive in a new way. Suddenly, we’re not just reading a poem, we’re experiencing it.

As we move from one poem to another, students stand in the middle of the three and take turns reading aloud about the trees, the sky, and the animals. It’s a miracle that a line of poetry matches the rhythm of the wind and that the sunlight makes the poem even warmer. It reminded me of something important: learning doesn’t have to happen behind a desk. Maybe the best learning doesn’t.