Correct critical thinking deficiencies

go through Terry Heck

As a culture, we face a crisis of ideas—that is, the harmful and persistent rejection and/or inability to think well and critically.

This is just an opinion, but I hope not a radical one. To clarify why this crisis exists—or even why I believe it exists—requires a comprehensive analysis of cultural, social, political, and other anthropological terms that extend beyond the scope of pedagogical thought.

First, browse the “discussions” on almost any social media about any culturally critical issue. If you disagree that such a crisis exists, the rest of this article is probably not worth your time. However, if we can assume that this statement is at least partly true, then we can see that our crisis in education as an industry is both a cause and a consequence of the above.

Education is both the cause and the result of thought. Education and ideas are, at least conceptually, as interconnected as the structure of a building and the building itself.

To a certain extent, this “crisis of ideas” is also a crisis of language and is related to the crisis of emotion. Related issues include deficits in utility, knowledge, patience, place, and cultural memory. But for our purposes, let’s discuss one of the core crises within the crisis: the shortcomings of critical thinking.

This is partly a question of the subject and quality of thought: what we think and how we think.

On the surface, education – in fact – is not about Teaching ideas It’s about content. This really shouldn’t be controversial.

The true face of education

Education is broadly divided into content areas and stratified by age. From a broad perspective, the overall structure can be thought of as a big grid: the columns are the content areas and the rows are the “ages”. We can also think the other way around, and not much will change.

Simply put, the formal education system in the United States is designed for people to learn (usually) four main categories of knowledge (math, science, social studies, and language arts) over a period of thirteen years.

These content areas tend to get more complex, but only intermittently specialize (e.g. “Science” becomes “Chemistry” even though Chemistry is still a science; for the record, I’m not sure why we don’t show at least a little foresight to combine the sciences and humanities into “new content areas” that aren’t content areas at all, but realizing this is crazy talk to most people will save my breath).

The point is, education – in fact – is about content, while mastery of content is about scores and scores that either lead to credentials (e.g. diplomas) or do not lead to credentials (e.g. diplomas) that allow for increasingly specialized studies (business, law, medicine, etc.) in higher education (e.g. colleges/universities) for the purpose of “career preparation” (which I have argued should not be School purpose).

The three most obvious components in most modern K-12 public education systems: teachers, content, and letter grades, with the first two often combined (e.g., “math teacher” or “art teacher.”) There are also very obvious educational components: students, tests, computers, books, walls, desks, hallways, groups, bells, calendars, blackboards and whiteboards at the front of the classroom, etc.

The above analysis is not comprehensive, and there are countless exceptions to learning styles and forms, but they are exceptions after all. Indeed, as far as I know, this overview is not misleading in describing modern public learning forms and spaces.

If the above is a more or less accurate summary of how humans learn in formal education, it should be at least somewhat clear that we have a problem.

A sort of deficit.

The McDonaldization of the Classroom

You can’t assess the quality of a “thing” without knowing what it’s supposed to do. This is simple for kitchen utensils, but challenging for art, emotion and people: clarifying education and what it “should be” is a very personal and “local” philosophy of teaching ideals to others. This is because of the nature of standardization.

In 1993, George Ritzer wrote a book called The McDonaldization of Society, which owed much to the previous work of many people, including Max Weber. This book explores the causes, effects, and nature of standardization through the lens of the McDonald’s U.S. restaurant chain.

McDonald’s isn’t the first company to take advantage of this standardization. In fact, industrialism itself – the backbone of 20th-century America – owes much to Henry Ford’s “popularization” of the concept. Whether or not you find a “problem” with industrialism, it is first and foremost a philosophical question.

George Ritzer takes core elements of Max Weber’s work, expands and updates them, and provides a critical analysis of the impact of changes in social structure on human interaction and identity. A central theme in Weber’s analysis of modern society was the process of rationalization. This is a far-reaching process in which traditional modes of thinking are being replaced by ends/means analysis focused on efficiency and formal social control.

For Weber, the quintessential expression of this process was bureaucracy. A large, formal organization characterized by a hierarchical authority structure, a well-established division of labor, written rules and regulations, objectivity, and a focus on technical capabilities. Not only do bureaucratic organizations represent a process of rationalization, the structures they impose on human interaction and thinking further this process, leading to an increasingly rationalized world.

This process affects every aspect of our daily lives. Ritzer argues that in the late twentieth century, the socially structural form of fast-food restaurants has become an organizing force that represents processes of rationalization and extends them further into the realm of everyday interactions and personal identities. McDonald’s in the 1990s exemplified this process.

Ritzer explains in the book that one effect of infinite rationality is irrationality: “Most specifically, irrationality means that rational systems are systems that are irrational. By that I mean that they deny the basic humanity, the human rationality, of those who work in or for them.”

This brings us back to the shortcomings of education and critical thinking.

Standardizing anything is a trade-off. I’ve talked about this dozens of times before –For example here. and here. There are many other posts, tweets, and articles out there because, in my opinion, it represents one of the inherent flaws in our modern learning design. In short, in Education as it isEvery student, regardless of background, race, gender, hobbies, family history, local needs, or family expertise, learns the same content in a similar manner—like an academic cafeteria.

The implicit hope in delivering a course to these students (i.e. all students) in this way (i.e. the ‘grid approach’ explained above) is that it will meet the needs of everyone. Its design is reasonable.

And the delivery method of this course (e.g., teachers, classrooms, books, apps, tests, etc.) is also designed appropriately. That is, both the curriculum (what is learned) and the learning and instructional design models (how it is learned) are designed to be practical: testable, observable, and deliverable to every student, no matter what. By design, public education is accessible to all students, everywhere, no matter what.

But what about thinking? Can critical thinking developed and applied by thinkers coexist in a standardized learning environment designed to promote mastery of the most traditional academic content for the widest range of students? It’s possible – but that’s probably not the best way to ask the question.

Is the purpose of education to promote emotion, curiosity, inquiry and critical thinking?

People drive tractors and ride in hot air balloons, but that doesn’t mean they’re perfectly suited for the task. Beyond education, our entertainment lies in the differences in functionality and application. But what about in education? Generations of students suffer from deficits.

What about critical thinking?

exist ‘What does critical thinking mean?? I said:

“Critical thinking is one of the first causes of change (both personal and social), yet it is shunned in schools—for no other reason than that it makes the mind question the form and function of everything it sees, including your classroom and everything taught in it. In critical thinking, thinking is simply a strategy for arriving at informed criticism, which itself is the understanding of one’s self. The starting point of the world around me and/or you. While functionally it can run parallel to the scientific method, science aims to achieve an unbiased, neutral and dehumanizing conclusion. In critical thinking, there are no conclusions; constant interaction with changing circumstances and new knowledge can lead to a broader perspective that provides new evidence to start the process anew.”

This brings us closer to a cultural deficit in critical thinking that is partly attributable to a parallel deficit in critical thinking in education.

People often debate whether we can “teach” critical thinking, but this seems to miss the point. Instead of asking whether critical thinking can be taught in schools—or even if critical thinking can be taught—we can start by asking what we lose if we live in a world where critical thinking doesn’t happen.

While entirely new formats, methods and reasons for learning may ultimately disrupt Education as it is From the outside, if we miss the old and solid education system, we can at least address the shortcomings of critical thinking by embedding it in the education system. This can be achieved in a variety of ways, but some results seem low-hanging fruit.

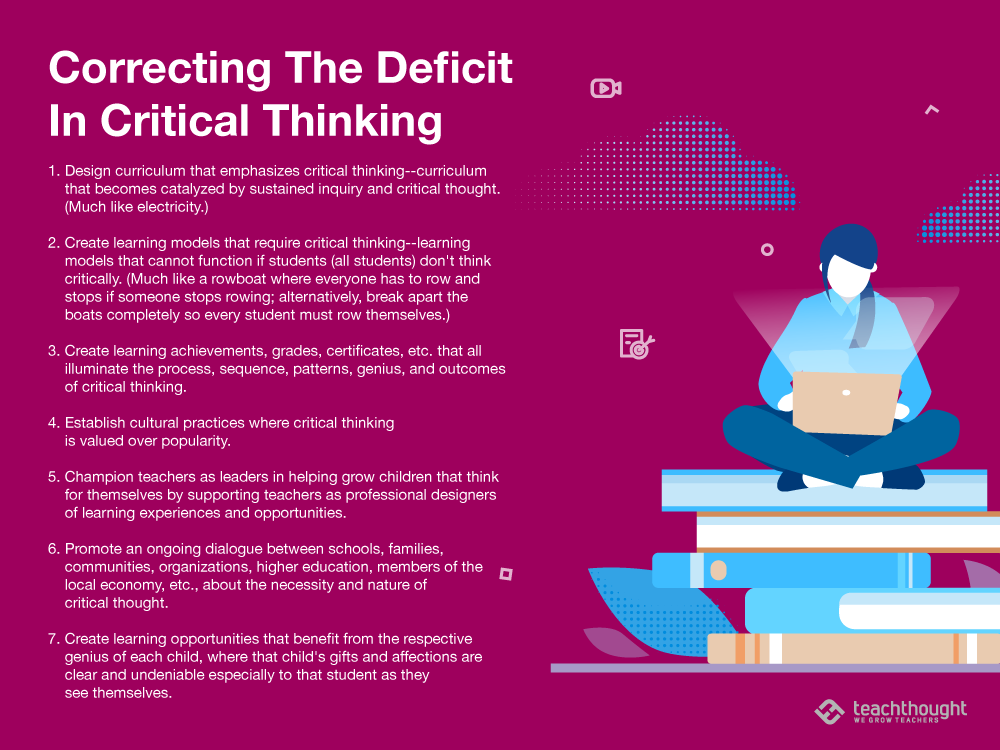

1. Design a curriculum that emphasizes critical thinking—a curriculum catalyzed by ongoing inquiry and critical thinking. (Much like electricity.)

2. Create learning models that require critical thinking – Learning models won’t work if students (all students) don’t think critically. (Like a rowboat, everyone must row and if someone stops rowing, stop; alternatively, break the boat apart completely so each student must row on his or her own.)

3. Create learning outcomes, grades, certificates, etc. that illustrate the process, sequence, pattern, genius, and results of critical thinking.

4. Establish cultural practices that value critical thinking over popularity. (Democracy might benefit.)

5. Support teachers as professional designers of learning experiences and opportunities, support teachers as leaders, and help children grow into independent thinkers.

6. Promote ongoing dialogue about the need and nature of critical thinking among schools, families, communities, organizations, higher education, members of the local economy, etc.

7. Create learning opportunities that benefit from each child’s individual gifts and emotions, which are clear and undeniable, especially for students who believe they are.

We could go on, but I’m afraid I’m getting too far away from the point: School because they are was not “designed” for critical thinking, and now, as a culture (and planet), we are suffering from the resulting deficit.

This means we may focus less on iterative improvements in education and more on education maybe so.