State lawmakers take aim at development projects in Santa Barbara. Now, the consequences

Last year, when a developer unveiled plans for a towering apartment tower near the historic Old Church, angry Santa Barbara residents jumped into action.

They complained to city officials, wrote letters and formed a nonprofit to try to stop the project. Still, the developers’ plans continue.

Then something unusual happened.

Four hundred miles away in Sacramento, state lawmakers quietly slipped language into an obscure budget bill requiring an environmental impact study of the proposed development — an effort that housing advocates claimed was an attempt to block the project.

The legislation, Senate Bill 158, was signed into law by Gov. Gavin Newsom but did not mention the Santa Barbara project by name. But the regulations are too detailed and specific to apply to any other development in the state.

The fallout was swift: Developers sued the state, and one Santa Barbara lawmaker, the new state Senate president, came under scrutiny for his role in the bill.

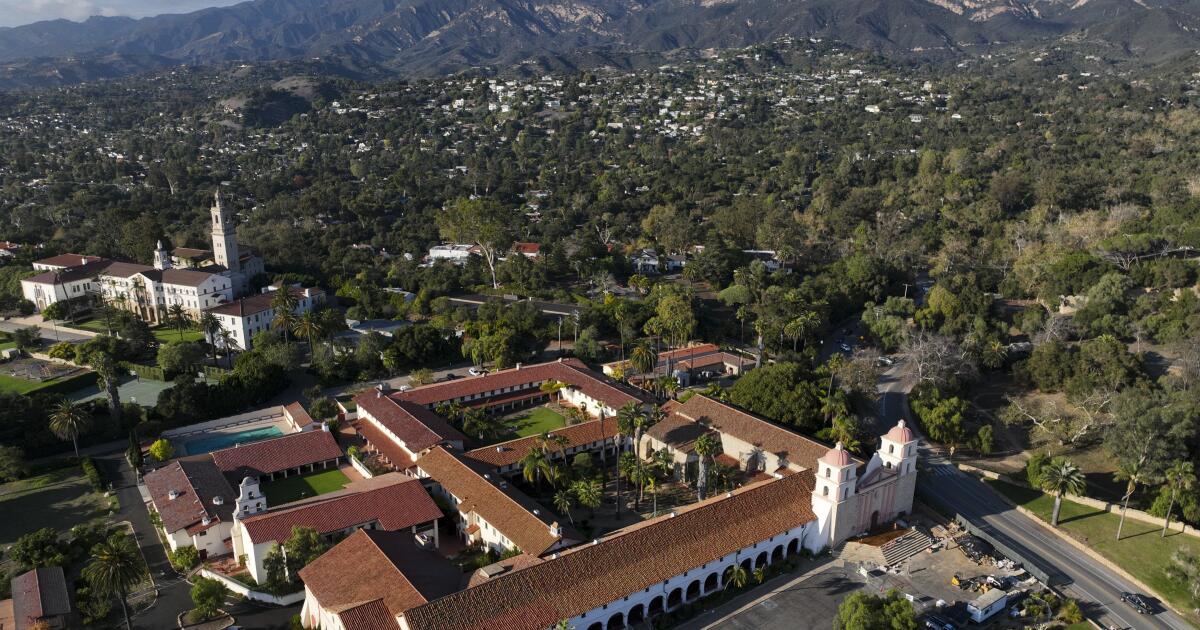

The current property is on the proposed site of an eight-storey apartment building.

(Kayla Bartkoski/Los Angeles Times)

The incident highlights the growing influence of the governor and state Legislature in local housing decisions and the battle between cities and Sacramento to address California’s severe housing shortage.

Faced with California’s high housing and rental costs, state leaders are increasingly passing new housing mandates requiring cities and counties to speed up the construction of new housing and ease barriers that hold back developers.

In this case, the law targeting Santa Barbara development projects has backfired, making it more difficult to build.

‘A terrible nightmare’

The fight began last year after developers Craig and Stephanie Smith laid out ambitious plans to build an eight-story residential project with at least 250 apartments at 505 E. Los Olivos Street.

The five-acre site is located near the Old Church of Santa Barbara and attracts hundreds of thousands of visitors each year.

Santa Barbara is a slow-growth haven where many apartment buildings are two-story and the Los Olivos project is considered a skyscraper. Mayor Randy Rowse called the proposal “a horrible nightmare,” according to local media site Noozhawk.

But developers have an advantage. California law requires cities and counties to develop growth plans every eight years to address California’s growing population. Jurisdictions need to identify areas where additional housing or density can be added.

If cities and counties fail to develop a plan by the eight-year deadline, a provision called a “Builder Remedy” kicks in.

It allows developers to bypass local zoning restrictions and build larger, denser projects as long as they include low- or moderate-income units.

When the February 2023 deadline passed, Santa Barbara was still working with the state on the housing plan. The plan was completed in December of that year, but did not officially come into effect until February 2024, when the state government approved it.

Opponents of the Santa Barbara development, clockwise from lower left: Cheri Rae, Brian Miller, Evan Minogue, Tom Meaney, Fred Sweeney and Steve Forsell.

(Kayla Bartkoski/Los Angeles Times)

The developers submitted their plans a month ago, in January. Since it includes 54 low-income units, the city can’t outright deny the project.

“The developers are playing chess and the city is playing checkers,” said Evan Minogue, a Santa Barbara resident who opposes the development.

He said resistance to change among California’s older generations has led the state to adopt “harsh, one-size-fits-all policies that force cities to do something about housing.”

Santa Barbara, a wealthy city that attracts celebrities, bohemian artists and environmental activists, has long struggled to maintain a small-town feel.

In 1975, the city council passed a plan that limited development, water use and traffic, and capped the city’s population at 85,000. In the late 1990s, UC Santa Barbara alumnus and actor Michael Douglas donated money to protect the city’s largest piece of coastal land.

The city is surrounded by the Santa Ynez Mountains and is dominated by low-rise buildings and single-family homes. According to Zillow, the median home value is $1.8 million. A city report last year detailed the need for 8,000 new housing units over the next few years, primarily for low-income families.

Stephanie and Craig Smith are the developers of the project, located at 505 E. Los Olivos Street.

(played by Ashley Gutierrez)

Assemblyman Gregg Hart, whose district includes Santa Barbara, supports language in the budget bill requiring an environmental review. He did not want to see the proposed development tower built on top of the old church and blamed the introduction of the Builders’ Remedy Act.

“This is a great example of how bad the ‘builder remediation’ system is,” Hart said. “Proposing projects like this undermines support for building density in Santa Barbara.”

Similar pushback has emerged in Santa Monica, Huntington Beach and other smaller cities as developers scramble to take advantage of the Builder Relief Act. A notable recent example flintridge canadaDespite strong opposition from the city, developers are moving forward with an 80-unit mixed-use project on 1.29 acres.

Still, the controversial law does not exempt developments from scrutiny under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), the state’s landmark policy that requires studies of a project’s impact on traffic, air quality and more.

However, the developer behind the Los Olivos Street project is trying to avoid environmental review because of a new state law that allows many urban infill projects to avoid such requirements. Assembly Bill 130, based on legislation introduced by Assemblymember Buffy Wicks (D-Oakland), was signed into law by Newsom in June.

When Los Olivos developers asked city officials whether to use AB 130 in their projects, Santa Barbara Community Developers Director told them in July 2025 that a CEQA review was necessary. AB 130 does not apply if the project is planned near creeks and wetland habitat or other environmentally sensitive areas, the director wrote.

Months later, the state Legislature passed a budget bill requiring the review.

Santa Barbara residents who opposed the project said they did not ask for the bill.

But they may have an easier time dealing with the project if a review finds that traffic from the development would overwhelm fire evacuation routes.

“We don’t want to come across as NIMBYs,” said Fred Sweeney, a resident who opposed the project, referring to the phrase “not in my backyard.” Architect Sweeney and others launched the nonprofit Smart Action for Growth and Equity to highlight the Los Olivos project as well as a second project planned by the same developer.

On a recent day, Sweeney stood near the project site and pointed at the cars lining the main thoroughfare. Although it’s not rush hour yet, traffic is already congested.

A ‘very strange’ bill

The bill passed by state lawmakers targeting the Los Olivos project is buried deep in Senate Bill 158, which references state law regarding infill urban housing development. Senate Bill 158 clarifies that certain developments should not be exempt from the law.

The bill states that there are no exceptions for “cities with a population of more than 85,000 but less than 95,000 and counties with a population between 440,000 and 455,000” as well as developments near historic landmarks, regulatory floodways and watersheds.

According to the 2020 census, Santa Barbara’s population was 88,768. Santa Barbara County has a population of 448,229. The project is located near a creek and the Church of Santa Barbara.

This controversial development fits the bill.

Monique Limón is President Pro Tempore of the California Senate.

(Myung J. Chun/Los Angeles Times)

A representative for Senate President Pro Tempore Monique Limon told CalMatters the senator was involved in crafting the immunity language.

During a visit to an avocado farm in Ventura last month, Limon declined to comment on her role. She cited the lawsuit and posed questions to attorneys. Gen. Rob Bonta’s office.

Limon, who was born and raised in Santa Barbara, confirmed that she did discuss opposing the development with Sweeney, who founded a nonprofit to fight the development.

She said the Los Olivos project had “a lot of community involvement and involvement.” “In terms of feedback, I understand that over 400 people have commented on it after reading the article… It’s a very public project.”

Limon also defended his housing record.

“Every piece of legislation I draft or review is based on the needs of our state but also with the perspective of the communities I represent — whether it’s housing, education, environmental protection or any other issue that crosses my desk,” Limon said.

The developers filed a lawsuit against the city and state in October, claiming SB 158 targets one specific project: theirs. The conduct is therefore illegal under federal law, which prohibits “special legislation” targeting a single person or property.

The residence is currently located on a proposed development site.

(Kayla Bartkoski/Los Angeles Times)

The lawsuit alleges that Limon pushed and steered the bill through the state Senate, arguing it should be overturned and challenging the required environmental review that could have added years to its timeline and millions of dollars to its budget.

Stephanie Smith, one of the developers, told the Times that the bill grew out of “protests from wealthy homeowners, many of whom acted as housing advocates until proposed housing was located in their neighborhoods.”

“As a former homeless student who worked full time and lived in my car, I know what it means to struggle to afford housing. Living without security or dignity has convinced me that housing is a basic, non-negotiable human right,” Smith said.

Public policy advocates and experts have raised concerns about state lawmakers using their power to interfere with local housing projects, especially when it comes to exempting them from legal provisions they impose on everyone else in the state.

“It’s hard to ignore when legislation is drafted in a narrowly tailored way — especially when that language comes late in the process, with little public input,” said Sean McMorris of Common Cause California, a good government group. “A bill framed in this way risks fueling public cynicism about the legislative process and the motivations behind narrow policymaking.”

Chris Elmendorf, a professor at the University of California, Davis School of Law who specializes in housing policy, called the bill’s specific language “very strange” and questioned whether it would survive legal challenges.

He expects to see more requests for exemptions from state housing laws.

“Local groups that don’t want the project are going to go to the Legislature for relief, whereas in previous eras they could get relief from the city council,” Elmendorf said.

UC Santa Barbara student Enri Lala is the founder and president of a student housing group. He said the bill went against the region’s recent housing support campaign.

“It’s really unusual,” Lara said. “This is not the type of behavior we would like to see repeated in the future.”